By Deryck Shaw, Wai Kōkopu Chair

The number of community catchment groups such as Wai Kōkopu has grown rapidly over the past 10 years throughout Aotearoa New Zealand. These groups vary geographically and in terms of their focus. Recent research by the Cawthron Institute and University of Canterbury (commissioned by the Ministry for the Environment in 2022), shows that two-thirds of waterways groups were formed in 2014 or later, with increases in 2017 and 2020 which seem to have occurred when the government updated their National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management.

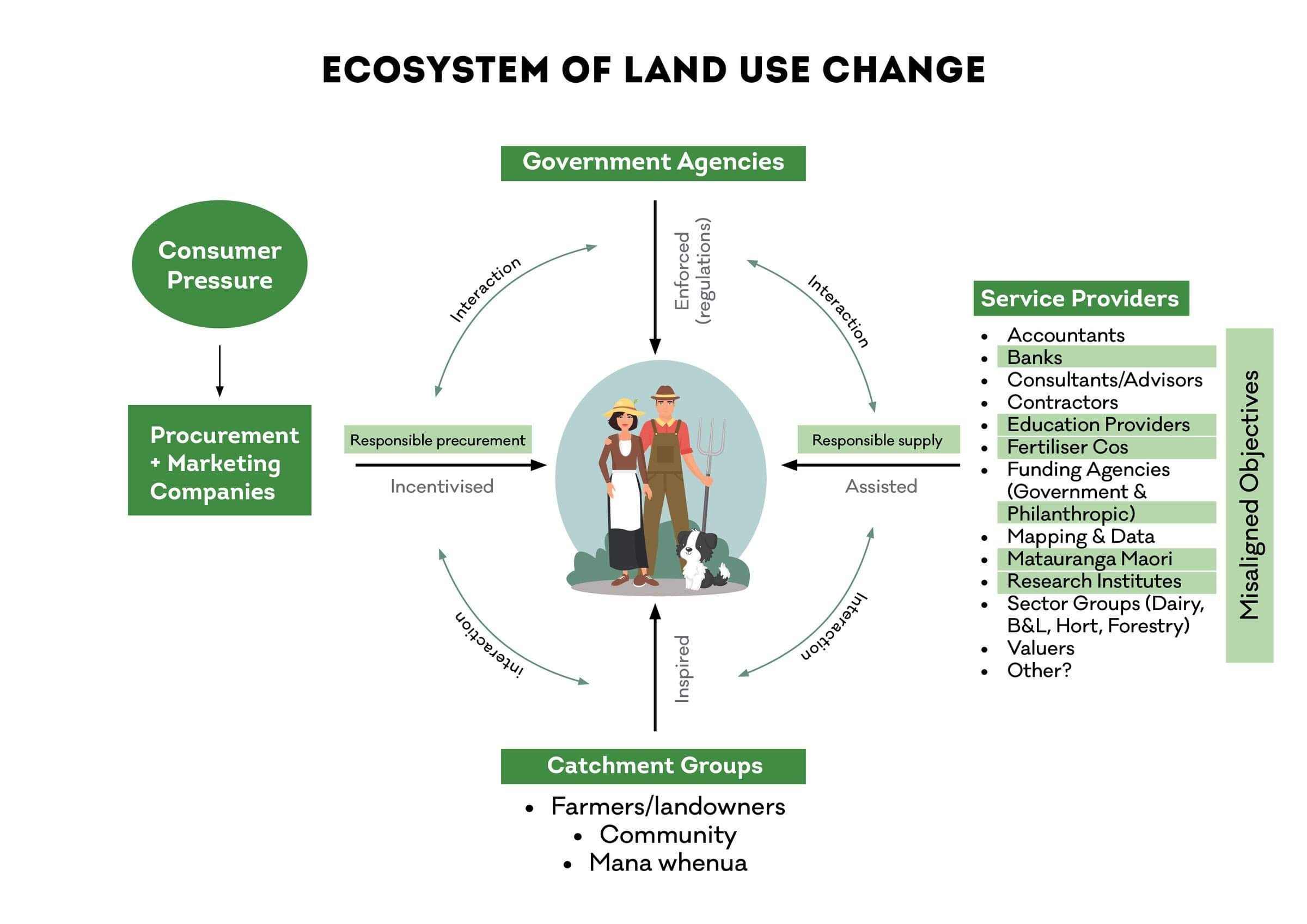

Catchment groups are important connectors, advocates and partners in a wider system of sustainable land use change.

These groups are diverse and make a powerful statement that communities are looking to improve a range of outcomes in their catchments. These include environmental, social, cultural and economic outcomes.

Wai Kōkopu has been established more recently than many of its peers and has taken a holistic view of the catchment to restore the mauri (life giving properties) of the Waihi Estuary. In many ways the group has been playing catch-up, given the high levels of E. coli and nutrients in the estuary. Taking a ‘whole of farm systems’ approach has been incredibly positive and has seen many farmers in the catchment review their farm management practices. In several cases this has improved their bottom line while resulting in less applications of fertiliser, water and lower stocking rates. The 15 lighthouse farmers in our catchment are exemplars of the opportunity that this presents.

However, there are several barriers to the work of groups such as Wai Kōkopu which include:

Funding to support ongoing efforts for a range of catchment programmes.

The complexity of working with a diverse group of partners and stakeholders in the catchment such as iwi, community groups, industry groups, statutory local and central government agencies, and research organisations trying to improve catchment health.

The level of knowledge available in the catchment to provide clear baseline evidence and prove the relationship between changing land use practices and likely environmental and other outcomes. This is particularly important given the pool of people who have the experience and knowledge to undertake this work in the county is limited.

Because the sphere of work is so large, endeavouring to identify priority areas to resource can become quite complex. An example for Wai Kōkopu would be the range of invasive weed species that exist in the catchment. Looking to make this a priority while trying to attend to other issues such as restoring fish passages and proving an evidential basis for reasons to lower farm inputs, is tricky.

There has been great work going on around planting for riparian management and biodiversity purposes. Overall, environmental monitoring will become increasingly important as catchment groups look to demonstrate the success of their various programmes in improving catchment outcomes.

There are always very practical activities that farmers have taken for many years such as retiring land and planting more diverse and economically viable feed and tree species which can also build greater farm resilience though biodiversity. Simple techniques such as fencing off and retiring erosion-prone land can lead to lower farm management costs.

Longer-term, farmers are moving to environment plans which again provide an opportunity to review the relationship between farm management practices and environmental, economic and other outcomes. Many farmers struggle with the high cost of these plans and the costs of implementing systems such as detention structures and wetlands. These often cost a lot to design and have less certain environmental and economic outcomes.

Overall, catchment groups provide an opportunity to work closely with communities to achieve agreed catchment outcomes. But they struggle to find the resources to support their often ambitious programmes. Therefore it is important they have good representation from the community, strong science and evidence behind their programmes, effective environmental monitoring, and a diverse funding base so they are not reliant on one or two funders. Incorporating lower impact farm management practices will continue to generate ongoing benefits for all.

The ability of these groups to work with iwi, regional councils, government agencies, industry groups and their communities, will become more critical in future. Technical advice will always be essential to apply resources where they can produce the most sustainable outcomes.

Seeing the work of these groups through visible activities like pest and weed control, planting, and environmental monitoring such as water testing, will provide the opportunity for greater levels of community engagement. The number of volunteers involved can often be seen as a proxy for community support and ensuring there are multi-year planning horizons for catchment work is important to ensure the longevity of various work programmes.

Like all matters these days, staying connected and engaged with communities will provide strong resilience for individual catchment groups once current volunteers and board members complete their service.